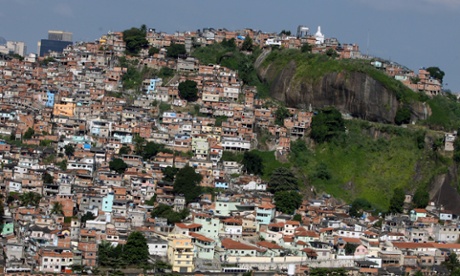

The writer, Simon Jenkins, correctly notes that "the essence of the favela sovereignty is local ownership." And he clearly gets the surreal nature of the cable cars, complete with white-gloved attendants, that the city installed over violence plagued Complexo do Alemao. How strange, then, that he doesn't quote a single favela resident -- despite the fact that one of every five people he passes every day lives in a favela.

In the same spirit, it's odd to find a picture of a normal young woman and her baby

walking in front of a colorful mural on an otherwise empty street, captioned "Life in the Cantagalo favela" -- as if it's bizarre and amazing to simply walk down the street.

What's more, as one of the commenters on the article points out, when Jenkins suggests that the so-called pacification program, which started in 2008, "rightly acknowledged that lasting improvements of favela living conditions required government control of law and order," he ignores the history of community-led improvements that have been made over the years and the fact that, for most favela dwellers, the police never have been a positive influence. Indeed, they've been responsible for lots of violence and killings over the years.

Similarly, when he suggests that "there has to be a compromise between gentrification and stasis. Somewhere in a freer property market lie the resources to update these places," he ignores the immense amount of resources that people already have invested. They built their homes -- building and rebuilding and rebuilding again over decades. They brought water and electricity -- stealing these essentials at first, sure, but making the investment to pipe and wire their communities and homes. Freedom to develop in the manner that Jenkins seems to advocate somehow always comes to mean freedom to evict. It's a nasty business -- and favela dwellers are quite understandably anxious about losing their homes. (I don't live in a favela, but I certainly was anxious when my landlord tried to evict me.) Besides, there's already a property market in the favelas -- people buy and sell homes all the time -- and it hasn't brought the Nirvana that Jenkins hopes for.

Jenkins is right that most of us who write about or study the favelas don't get sewers built. But this is an issue of local organizing. I have argued for almost a decade now that sewers are secure tenure, that organizing for infrastructure is a hugely important strand of a strategy for the future. But organizing doesn't come from the outside. Brazil's favelados spent decades remaining under the radar because they were afraid that powerful political and development interests would conspire to push them out. Now, as those same interests are using the excuse of the World Cup and the Olympics to wage war on them, they have to learn how to emerge. This is a difficult process, and it is happening in the most dire of times.

2 comments:

I havent read the Jenkins article but I agree that most "favela thinkers" never spent much time in the field, nor developed long term relations with the places they analyse.

To flert with disourse about favela is different than making a living in precarious conditions. Generations are created in poor conditions. In many cases, especially in favelas that are not close to the rich neighborhoods, people wish to move, to change their life scenarium to a regular part o the city.

Changes are being made in favelas of Rio, however the quality of those reurbanizations are questionable, highlighting the sad role of State Government in all this.

thanks ,,,,,,,,,

Post a Comment